Idi Amin: “We Africans used to carry Europeans, but now Europeans are carrying us. We are now the masters … They came from Britian and wanted to show that I really have power in my country.”

Idi Amin, the former president of Uganda, had a dream in August 1972. “I have dreamt,” he told a gathering in Karamoja, northeastern Uganda, “that unless I take action, our economy will be taken over. The people who are not Ugandans should leave.”

He left Karamoja by helicopter and stopped at the Tororo airstrip in easternUganda. He had sent word that he wanted to address the army. There, he announced the dream again to a hurriedly organised parade by the Rubongi military unit. Some Asians were thrown into a panic. Others thought Amin was bluffing.

P. K. Kuruvilla had just bought a building in Kimathi Avenue in downtownKampala, the capital. It was a home for his insurance company, United Assurance. He says: “We invested all the money into buying the building. We took a loan from the bank, I had a house in Kololo and I mortgaged it to raise money for the building.”

Then President Amin announced the expulsion. “I thought he was not serious,” says Kuruvilla. “I had put all my money plus a loan into the United Assurance property. We had confidence that we were going into a new era.”

But Idi Amin meant ever y word. Ugandan-Asians had to leave in 90 days. Kuruvilla first sent off his family and lingered around just in case Amin changed his mind. But Amin`s “economic war” was real.

The Asians had to make arrangements and hand over their business interests to their nominees. The arrangement among most Asian families was that one would be a Ugandan, another Indian, another British. So the non-Ugandans transferred their businesses to the Ugandans.

The British High Commission became a camp. Many of those with Indian passports wanted to go to the UK. The three months` deadline was fast approaching.

Meanwhile many Ugandans celebrated and lined the streets daily to chant, “Go home Bangladeshi! Go home Bangladeshi!”

Colonial Uganda had strongly favoured Asians. Many arrived with the British colonialists to do clerical work or semi-skilled manual labour in farming and construction. They had a salary, which became the capital to start businesses.

Aspiring Ugandan entrepreneurs on the other hand faced many odds. The British colonial government forbade Africans to gin and market cotton. In 1932 when the Uganda Cotton Society tried to obtain high prices by ginning and marketing its own cotton and “eliminate the Indian middleman,” it was not allowed.

The banks – Bank of Baroda, Bank of India, and Standard Bank of South Africa- did not lend to many Africans. As such, the Africans could not participate in wholesale trade because the colonial government issued wholesale licenses only to traders with permanent buildings of stone or concrete. Very few African traders had such buildings. It was clear that the colonial wanted native Ugandans to remain hewers of wood and drawers of water.

By 1959, when a trade boycott of all foreign-owned stores was pronounced by Augustine Kamya of the Uganda National Movement, Africans handled less than 10% of national trade. Ambassador Paul Etiang served as Amin`s minister for five years. He was the permanent secretary at the ministry of foreign affairs in 1972.

In an interview with New African, he explained that the expulsion came about partly because of the racial segregation inherited from Uganda`s past.

British apartheid

Up till independence in 1962, there was an unwritten but trusted social order in the colonial administration where Europeans were regarded as first class, Asians as second class, and Africans as third class.

For example, in trains there was a first class coach for Europeans and a few Asians, and there were coaches for Asians, and coaches for Africans. Apartheid did not start in South Africa or the US; it started with the “mother country”, Great Britain.

The same order prevailed with other facilities such as toilets. The segregation was not supported by law but it was observed in practice. Africans were not expected to go to the Imperial Hotel (The Grand Imperial Hotel in downtownKampala). There was a sign outside the hotel that stayed there until 1952. It read: “Africans and dogs not allowed”. The waiters were Asians.

“Come independence in 1962,” Ambassador Etiang explains, “one significant provision in the independence constitution was an article which stated that those people who were not Ugandans as at Uganda`s independence on 9 October 1962, had two years to make up their minds, whether to become citizens of the new Uganda or adopt the status of British-protected persons, in which case the latter would have a British passport.”

Many Asians at the time applied for British citizenship but because business was good in Uganda with no competition from the locals, many did not leave.

In 1969, Britain tabled a revised version of its Immigration Act, the Patriot`s Act. Commonwealth passport holders would need a visa to enter Britain.Britain was compelled to pass that Act as a condition for its entry into the European Economic Commission (EEC). Now, it was only citizens of member states of the EEC that had the right to travel to Britain without a visa.

“Commonwealth members reacted to it very strongly,” Ambassador Etiang recalls. “This is what brought about the immigration discussion in Uganda.”

The Ugandan government, then under President Milton Obote, started asking: “How do we deal with all these Asians? If Britain was making rules barring us from opportunities in Britain, then we also have the right to have our own rules to regulate those who are coming here.”

That was when Uganda, Kenya, and Tanzania realised that they needed their own Immigration Acts, and the first Immigration Acts were subsequent passed that year in reaction to the British Patriot`s Act. By 1971, the issue of Asians being Ugandans or not, remained unaddressed beyond the provision in the 1962 Constitution. “But this is what I believe triggered the expulsion under Amin,” says Ambassador Etiang.

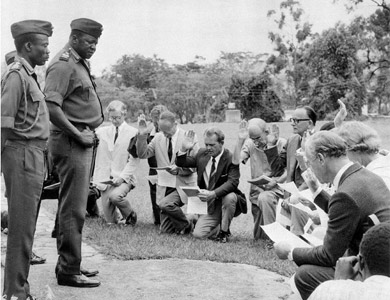

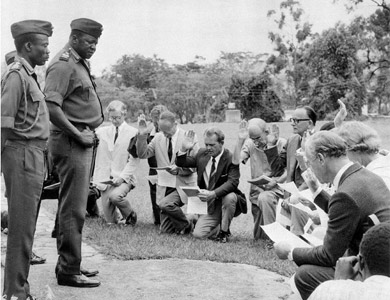

His Excellency President for Life, Field Marshal Al Hadji Doctor Idi Amin, VC, DSO, MC, Lord of All the Beasts of the Earth and Fishes of the Sea, and Conqueror of the British Empire in Africa in General and Uganda in Particular. Idi Amin at swearing-in ceremony, October 02, 1975. The Photographer: Unknown/Bettmann/Corbis.

The spark

The head of the Religious Services at the time, Col Khamis Safi, was from the Nubian tribe and a Muslim like Amin. Safi was the son of a man believed to have walked to Mecca, on pilgrimage, in 1917. It is a popular Nubian story. Because he survived the treacherous journey by land, he was deemed to have been a holy man. And because he was holy even his children must be holy. Khamis Safi was therefore an obvious choice to be head of Religious Services.

“By 1972,” Ambassador Etiang recalls, “Khamis Safi was usually the last person to visit Amin every day at State House. On 4 July 1972, I happened to be among the last three to leave. There was Khamis Safi and Mustafa Ramathan, who was the minister for cooperatives. We were having a light chat when Amin came in.

“Khamis posed a question to Amin: `Afande, have you ever asked yourself why God made you a president?` Amin replied by asking Khamis: `What do you mean?`

“`God appointed you president,` Khamis repeated. `There are many injustices in this country. Each tribe has a place they call home. Even Etiang here, the Itesots have a place. But have you ever asked yourself, where do the Nubians come from? As far as I know God made you president to rectify the wrongs that have been handed to Nubians in this country. We are the ones who brought Captain Baker here, we are the ones who founded Kampala. Kampalais Nubian territory.`

“Amin was listening. You should have been there when this supposedly holy man was talking to Amin, he would be docile,” said Etiang.

Amin said, maybe it is true. But Mustafa Ramathan challenged the argument that Kampala was Nubian territory.

But Khamis insisted that Nubians too needed a place. “We brought the Muzungu (white man) here on our backs. He set up camp at Old Kampala. This place is ours.”

Amin said, “OK, we`ll think about it.”

Three weeks later, Amin left for Karamoja by helicopter. There, he revealed that he had had a dream that what Khamis had said was true. That God had revealed to him that unless he obeyed the advice of the holy son, Ugandarisked being taken over by the imperialists.

“I believe that was the origin of the expulsion,” Ambassador Etiang says. “Once you told Amin something and he liked it, he would keep it to himself and then later put it in his own way like it was his idea.”

When Amin told the cabinet about the expulsion, it was greeted with scepticism. The civil service received the implementation orders as a cabinet directive. The attorney general was directed to draft an expulsion order. Amin was later told he could not expel all the Asians because some were Ugandans.

“I met Khamis at State House again,” Ambassador Etiang remembers. “He told Amin in Kiswahili that what you have done is very good but if you want to remove this tree from here, you don`t just cut off the branches. The idea of only noncitizens leaving is like a branch. Remove the whole tree. An Indian is an Indian. He can have three passports at a time. All of them could be with two or more passports. Amin said okay.

“The Asians who suffered a lot are those who professed to be Ugandan because while the other ones had three months

“Once you told Amin something and he liked it, he would keep it to himself and then later put it in his own way like it was his idea.”

© Copyright IC Publications 2012. All Rights Reserved.

All Posts

All Posts